By Daile Cross ()

They sit together on the floor at the back of the classroom. Playing with Lego. Two teenage boys intent on the colourful little pieces spread across the carpet.

They barely look up from their activity as we enter, a colourful classroom like any other.

More boys sit chatting animatedly at a table together at the front of the room, they’re maybe 14 or 15 years old. Another leans over a book as he receives the personal attention of a teacher.

One teen tells us not to bother about the two classmates on the floor.

“They act like babies, playing with toys,” he says.

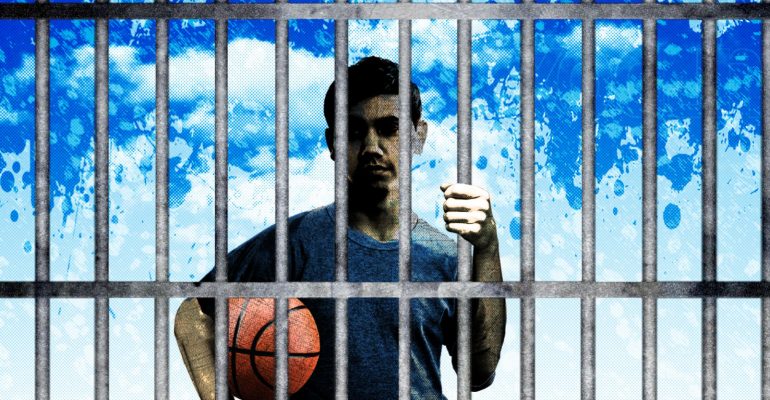

Across the yard, other teens play a competitive game of basketball against students from a school not far away. They cheer with enthusiasm as one boy from the home side scores a three-pointer just before the fulltime buzzer.

The scenes are the same as could be witnessed at any Australian high school.

Except the Banksia Hill Detention Centre is not a school. The young people are not here by choice. Huge concrete walls surround the site.

Those that reside at the centre on the outskirts of Perth retire to cells alone at night. Concrete cells with a shower, small TV, a bed.

The majority arrive at the centre traumatised by a life of neglect and abuse. An increasing number are arriving in the throes of psychotic episodes.

Between 60 to 70 per cent of the jail’s population is Aboriginal.

The “notorious” Banksia Hill has long been criticised as a “tinderbox” by the custodial officers’ union. There have been riots, the most serious in 2013 when a mob armed with weapons including rocks and smashed glass wrecked 100 cells.

Last year officers used stun grenades and pepper spray on a small group who went on a rampage, with specialist officers wearing helmets and using shields called in.

Many argue the centre’s set-up is fundamentally flawed. That housing 10-year-olds alongside young adults who may have committed violent crimes flies in the face of best practice. The revolving door, where more than half of the youth released end up back in the justice system within a year, points to a system that needs change.

Human Rights Law Centre director of legal advocacy Ruth Barson recently spoke out against the use of weapons like laser-sighted beanbag shotguns at the centre in 2016 and 2017, comparing the centre to the Northern Territory’s Don Dale.

No other state houses boys and girls, sentenced and unsentenced, from 10 to 18 years old, and from all regions, in the one facility.

Earlier this year a ground-breaking study found a shocking level of largely undiagnosed brain impairments in the Banksia Hill prison population, prompting many to question whether these kids deserved to be incarcerated at all.

The Telethon Kids Institute found 90 per cent were affected by significant brain impairments, and uncovered an unprecedented level of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder for a juvenile prison. More than a third had FASD, yet only two of the 36 had been previously diagnosed.

The researchers said proper diagnosis on the first interaction with the justice system was essential and would mean guards may understand some behaviour came from an underlying organic brain injury.

“It’s not wilful,” Clinical Associate Professor Raewyn Mutch said.

“It’s a behaviour by accident of how your brain works.”

As the system stands, those working at Banksia Hill rely on the courts to require a young person be assessed for FASD. If a child is suspected of having the condition once already at the detention centre, staff have to refer the child back to the court to consider ordering an assessment.

The Telethon Kids Institute’s Professor Carol Bower, who led the Banksia Hill Project, said there had been widespread interest in the research team’s findings and the custodial officer training they had developed, with other jurisdictions in Australia keen to either replicate the Banksia Hill study in their own facilities, or use the team’s training resources.

“The impairments discovered in our study are likely to be representative of the experience in juvenile justice centres across Australia, and also to be reflected in the adult prison population,” Professor Bower said.

“Although we are not currently undertaking similar studies elsewhere in Australia, team members including paediatrician Raewyn Mutch have met with the Queensland Department of Youth Justice to discuss replicating the study in that state’s juvenile detention facilities.”

The people who work inside the facility say they are making a concerted new effort to change how things are done, for the sake of the young people in their charge.

Trauma-informed care: ‘stabilise them emotionally’

The centre’s assistant director, Gavin West, comes from a career in child protection.

He is attempting to change the way in which the youth are cared for, putting a new trauma-informed model of care into practice which aims to speed up the assessment of young people with complex needs when they first arrive at the centre, and then better target interventions to help them cope.

The new model of care aims first to stabilise the child entering the centre, helping them regulate their emotions and mental state. Then the focus changes to engaging them in the programs, education and activities available. After this their mental health could be properly assessed, he says.

The 72-hour program of intensive support and assessment for children with complex needs brings specialists together to exchange information and develop a trauma-informed and culturally appropriate personalised care plan. This multidisciplinary team includes a psychologist, mental health nurse, education officer, Aboriginal welfare officer, and a case management coordinator.

Previously specialists and agencies had been coming to Banksia Hill separately, working as “silos”.

The new structure would mean the child benefited from consistency, with the programs and treatments they might have been engaged with outside now continuing inside. The assessment would be completed faster, but would have to rely on previous assessments by other agencies as well.

“The young person is part of the process and have their case managers from outside come in,” Mr West says.

“This helps stabilise the person, leading to shorter bursts of disregulation.”

Mr West also wants to develop smaller therapeutic communities for kids in the centre.

But the new model of care doesn’t come with new money. Or new staff.

We have had a lot of kids come in here who are actively psychotic. They’re delusional, they’re seeing things, they’re hearing things, they’re extremely paranoid.

Clinical forensic psychologist Kristy Down

It is expected to be delivered within the facility’s existing annual budget and will be subject to final endorsement by the Corrective Services Commissioner, although the minister says it’ll be in place permanently later this year.

“If any additional funding is required, a specific funding proposal will be developed,” the department advised.

Mr West’s job is not an easy one. He is tasked with dealing with young people who have fallen through every crack, landing in detention.

He says the government must work out how to intervene at the earliest point in these children’s lives.

“It’s a whole process, starting with community health organisations,” he says.

“That’s the complexity of what’s in front of us.”

It’s not enough: multi-pronged diagnosis team needed

Professor Mutch said the Telethon Kids Institute’s findings highlighted the vulnerability of young people within the justice system and the significant need for improved diagnosis to guide and improve their rehabilitation.

“What we would now like to see are comprehensive, multi-disciplinary assessments being undertaken for all young people on entry to Banksia Hill, to identify their strengths and difficulties and help staff understand how best to manage and help these young people,” she said.

“At a minimum, the team undertaking this assessment should include a paediatrician, a neuropsychologist, a speech pathologist and, ideally, also an occupational therapist.

“These assessments should be shared with relevant staff at Banksia Hill and in the community, to ensure management of the young person in question, and any interventions, take account of the young person’s specific neurodevelopmental profile.”

When WA Minister for Corrective Services Fran Logan was asked about the expert’s call for the suitably staffed diagnosis team, and whether the government would commit any new funding to the centre for staffing or new programs, his reply pointed to the establishment of a new Community Safety and Family Support Cabinet sub-committee.

He said a new period of cooperation with organisations including the Institute had begun, but Banksia Hill was an “unstable facility with no direction by the previous government”.

“A new model of care will be in place towards the end of this year but a series of pilot programs have already been introduced, which include behavioural support planning, special needs behavioural care planning and cultural programs by Aboriginal elders,” the minister said.

“The Telethon Kids Institute study confirmed what the staff had long suspected about alcohol abuse and mental impairment, and highlights the extreme challenges the staff and detainees face.

“The centre’s work with the institute continues and staff have been trained to better recognise, understand and respond to young people with suspected neurodevelopmental impairments.”

The young people at the centre had committed crimes that hurt innocent victims and a detention centre could only do so much to address systemic issues, he wrote.

“That is why the McGowan Labor Government is bringing government agencies together to address issues that, in some cases, have been present for generations.

“A Justice Planning and Reform Committee that includes the Department of Justice and WA Police is also looking at how we can reduce incarceration rates and how our custodial estate is structured.”

The Institute’s researchers said further investment in state-wide primary prevention programs to reduce and prevent pre-natal alcohol exposure and other causes of neurodevelopmental disorders was needed, earlier assessments and best practice interventions for children and young people who display difficulties – well before they end up in juvenile detention – and assessments for the siblings of young people who become involved with justice services.

“It costs over $200,000 a year to keep one young person in detention in Western Australia,” Professor Bower said.

“A relatively small investment in multidisciplinary assessments, evidence-based interventions and different ways of working to keep young people out of youth detention will result in rapid savings.

“Long-term social benefits are likely to flow to the young people, their families and the community, and economic benefits including from reduced recidivism and associated enforcement costs.”

The Banksia Hill centre has one full-time mental health nurse on site, a team of six psychologists, and a visiting child psychiatrist supports the on-site team.

A proposal for funding to have speech pathologists working at the centre has been submitted.

‘Life has punished these kids enough’

Clinical forensic psychologist Kristy Down, who quit a job working with “end-of-the-liners” in adult prisons for the more rewarding task of helping to rebuild the lives of young people at Banksia Hill, seems weary as she talks about her efforts.

“I think life has punished a lot of these kids enough,” she says.

“The system has failed so many of them. We want to provide a different experience. For them to have justice and fairness and every opportunity, because a lot of them haven’t had that.”

Ms Down describes the children as incredibly resilient. She says a lot have developed unique skills to manage the world they come from, where often they are exposed to systemic traumatic events.

“I really am impressed by some of the young people in here, wondering how they have survived and made it,” she says.

When you see a kid that’s had a really hectic life, and then can actually start to see them see a light at the end of the tunnel, it’s amazing.

Gavin West

“That is more the perspective we take, they have incredible resilience and we try to build on that.”

Those running the centre say the mental state of the youth arriving is worsening, a reflection of what is going on in Australian society.

“Recently we have had a lot of kids come in here who are actively psychotic,” Ms Down says.

“They’re delusional, they’re seeing things, they’re hearing things, they’re extremely paranoid.

“They are quite violent and quite aggressive with staff. They’re not rational, you can’t tell them it’s going to be okay.

“They present huge challenges for the staff in here, because the staff here are not mental health clinicians and we don’t have a facility that is a health facility as such that will take our young people. Because we don’t have a secure mental health facility for youth.”

Ms Down tells how some children may have had piecemeal engagement with different services, “but if we are going to help them make a 360 we need the complete picture”.

Through the new model care staff now have a sense of who that young person is, she says.

Before, custodial officers treated them “all the same”, and thought if you just keep repeating instructions long enough the child would learn.

“Now staff have a better sense of what triggers kids off, they’re just more aware of who they are as a person rather than just as another detainee,” Ms Down says.

A one-size-fits-all approach could not work when some of the kids coming in could not comprehend simple instructions.

Mr West says communication and comprehension difficulties are common. “When we give a child an instruction today, thinking they will retain it, they don’t retain it, they may not retain it for five minutes,” he says.

“Also they may actually not actually hear it. Or comprehend it. Their communication is seriously impaired.”

The situation is even more complex for youth coming to Banksia Hill from remote areas of the state.

“When you bring a kid in from Derby, or Fitzroy, or Halls Creek who has had no engagement of the level required to help them progress in their development, and then they come in here for offending, we are picking up a person that is, I would say, at close to ground zero,” Mr West says.

“There’s a lot of work to be done.”

Time to look ‘behind the curtain’

The man whose position as Western Australia’s Commissioner for Children and Young People means he has the weight of the welfare of society’s most vulnerable sitting heavy on his shoulders says it is time the community peered behind the curtain; the one that separates the mainstream from the forgotten families and children who remain locked in disadvantage.

“There are growing numbers of children and young people in particular who are being disadvantaged and are vulnerable through no fault of their own,” Commissioner Colin Pettit says.

“It’s a wake-up call for all agencies to have a look at how do we start to identify children with neurological difficulties, not just FASD, but a range of neuro-difficulties that we know will lead them into trouble. If we know that already we need to put early interventions into place, right across the board.”

Mr Petitt said New Zealand more than halved the number of children and young people being placed in detention.

“We should be looking internationally to see how we divert young people from going to Banksia Hill in the first place,” he says.

“When young people are getting themselves into trouble often they don’t start with major crime, it’s often petty silly behaviour that causes them to come to the attention of police in particular, at that point the police need to be empowered to say ‘look we can put them into a program with a particular non-government entity where they run through a program of self help’.”

The WA State Government announced a new $20 million program which aims to pair vulnerable families with a service worker to help them tackle issues including substance abuse, housing problems, domestic violence, mental health issues and school attendance.

Premier Mark McGowan said the Target 120 program would be rolled out over four years, beginning in Armadale in October.

“Target 120 holds those young people to account for their actions but also provides focused and co-ordinated intervention to address underlying issues,” he said.

Back inside

“Young people, to blame them, I mean, they’re children,” Ms Down says.

“We as the adults have to be responsible for them and managing their behaviour. So when they’re not behaving, rather than going ‘what’s wrong with that kid?’ we should be going ‘what are we doing wrong with that kid?’

“They’re still developing … there is still so much opportunity to set a different path. That’s why I love working with young people. I’ve worked with the end of the line.”

“It’s goosebumps stuff,” Mr West says.

“When you see a kid that’s had a really hectic life, and then can actually start to see them see a light at the end of the tunnel, it’s amazing.”